General

This work is a joint report prepared by the Dutch merchants W.A. Brahe and N.S. Muij on the ship Het Pasgeld, sent on 8th May 1756 for purposes of negotiating trade arrangements at the Sindh port, on the mouth of the Indus, called by the Dutch and other Europeans as Diewel-Sindh. The informative part of the document comprises the following:

- Items of import and export to and from Sindh, quantities imported, prevailing prices, and list of countries to which goods were exported from Sindh.

- Some reflections on the economic conditions and also law and order situation in Sindh.

- The Dutch, the English and the Portuguese rivalries for trade, and the difficulties the Dutch had to face with the two other nations.

- The attitude of local states towards foreign traders and methods employed by them to win favors.

- Custom duties, powers of custom officials, and the Governors of port.

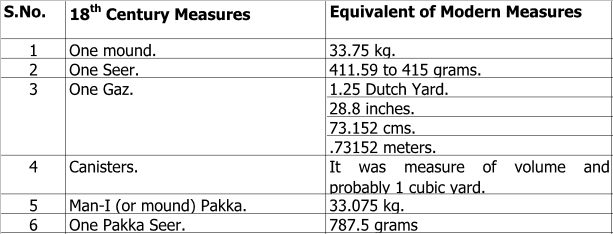

- Weighs and measures.

- Historical geography of Sindh in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as mentioned in the report.

- Grant of parwanas for establishment of trade, opening up of factories and custom remissions.

- Names of traders, governors of port and trading agents.

- Customs and manners.

The purpose of this introduction is to give a simple and brief account of each of the above and also an account of rivalries, the tactics used there in, and the outcome during different periods in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and discuss in some detail the articles of trade and their utility.

Portuguese in Sindh.

In the 15th century Venice had developed as the most important trading centre of Europe. It imported Eastern goods and spices from India, Southeast Asia, java and China through Arab merchants. In the 15th century Ottoman Turks occupied Egypt, Syria, Arabia and Iraq and cut off this trade route.

Europeans started searching alternative routes to Eastern trade as the Turks had put heavy duties on them through their territories. The Portuguese were the first European nation who discovered India via Cape of Good Hope in 1498. They soon established their factories or warehouses on important coastal ports and by export of goods to Europe became a rich nation. All the other European nations envied them but were kept away from East by the strong navy of the Portuguese who thus controlled the trade of India, Southeast Asia, China and the Philippines.

The Portuguese had established a factory at Lahri Bundar by about 1510 AD, with or without permission of the Samma rulers of Sindh. They had done the same along the western coast of India and the whole of Southeast Asia. For the whole 16th and first half of 17th century, the Portuguese were so powerful that the Indian Ocean was called the Portuguese Sea. They carried out substantial share of Sindh’s trade abroad and also brought goods from abroad. The monopoly was achieved by:

- Occupying strategic ports or points and forcing the local governments to sign treaties, giving the Portuguese the right to establish factories, carry out trade, have concessions and even monopoly of trade.

- Building well fortified forts at ports and bombarding boats of any other agency attempting to trade.

- Like pirates capturing the ships of other trading communities on the high seas and looting, burning or taxing them.

- Local business and sea-faring communities were converted into buying and selling agents of the Portuguese as Portuguese were not masters of the land as they were of the sea.

- Creasing terror among the crew of captured ships, so that they never sail with cargo ships of opponents of the Portuguese.

- Helping the Indian States in local feuds and wars, against one another.

- Keeping the maps of sea routes secret from other sea-faring nations of Europe.

- Keeping away the Arab merchants of the coasts of India, Africa, Persian Gulf and countries around Persian Gulf.

All major ports along the Indian coasts, Southeast Asia and Indonesia, were thus occupied. Philippines and Sri-Lanka (Ceylon) were conquered and ruled directly. A number of islands and island cities were captured, fortified and ruled directly. African coastal ports too were subdued. Spain was the only ally. The Pope under a treaty between these two countries had allowed Spain to occupy the whole of Americas except Brazil, which along with Eastern countries of old world was to be monopoly of the Portuguese. Their supremacy lay in huge ships which looked like forts and were fortified with guns. Guns were not known in the East and when they became known none of the rulers, including the Great Mughals, thought of building ships. The Portuguese did not have enough man power to fight on the land but they could make all the coastal States, land-locked. No ruler including the Mughal emperors could challenge them on the sea for more than a century and a quarter since they came to India.

For slightly over a century, after the discovery of America in 1492 AD, by Columbus, and of India in 1498 AD, by Vasco da Gama, they had complete monopoly over the seas of the world. The kings of Spain and Portugal were pioneers of this imperialist monopoly of trade. Then they crumbled. Among the reasons for their loss of monopoly, one was the British defeat of Portuguese and Spanish Armada, but much more important than this was the loss of Portuguese manpower. The kings of Spain and Portugal in a religious zeal had allowed their men to convert the subdued populace to Catholic faith and marry among the converts. The Portuguese married Indians, Ceylonese, Southeast Asians, Spaniards and the Red Indians. The next generations were neither as vigorous nor able-bodied nor had the European technology and zeal. Continuous supplies of man power form these countries for the two nations over a century exhausted this important resource, and the collapse, when it came, was sudden and complete. It was in fact the absence of Portuguese and Spaniards’ woman power in the territories they occupied that led to this end.

Upon their down fall the lead was taken by the Dutch, followed by the English, as subsequent paragraphs show.

Portuguese-Dutch Rivalry.

The rivalry between the Portuguese and the Dutch in the Eastern trade had historical reasons which are summarized below:

a) The Portuguese, a small nation, could not handle the distribution of their East Indian produce in Europe, but allowed the Dutch to act as commission agents and thus helped their most determined future rivals in their own downfall. With the monopoly to the Eastern maritime trade the Portuguese had allowed their mercantile navy to deteriorate. Philip II, King of Spain, became King of Portugal too and annexed it in 1580. This arrangement reduced Portugal’s power in the East and well as in Brazil.

b) In 1588 AD the Spanish Armada sent by Philip II against England was destroyed by a storm in the English Channel and, being further harassed by English ships, was forced to go around the British Isles. Having no route maps, their ships hit against rocks and 70 warships, out of a total of 130, were destroyed in this expedition.

c) The Dutch had rebelled against Phillip II and therefore were no longer able to act as middlemen between Spain and Baltic countries or to obtain spices in Portuguese ports. They, therefore, favored their rise as a naval power and to have direct relations with spice producing countries. The Dutch developed fast ships. Combining trade with piracy they did not hesitate to attack the Portuguese ships. With 10,000 sailors, the ‘sea beggars’, as they were called, became the sea kings. They soon made Amsterdam in the tradition of old Venice and began to replace Lisbon and Seville as great centers of trade.

d) The Portuguese opposed trading privileges to the English or Dutch from Akbar’s times, black mailing them as pirates, thieves and spies.

e) Surat’s English chief Middleton’s defeat of Portuguese vessels from Gujarat to Red Sea in 1612 created the prospect that new comers i.e., the English or the Dutch, may challenge the Portuguese command of the sea.

f) Downton (English at Surat) was prompted by Mugarabb Khan, Governor of Surat, in 1614 to attack the Portuguese. He was not ready to take offensive but was ready to defend himself which he did in 1615 with great loss to the Portuguese. The same governor had also asked Dutch at Masulipatam, in 1614, to help him against the Portuguese. Prince Khurram, whose governorship of Gujarat, included Surat, was in favor of the Portuguese in 1615, but in 1618, Roe secured a far man or grant from him, giving them reasonable facilities for trade. This reflects Middleton, Best and Downton’s efforts to defeat Portuguese, which tipped the balance slightly in favor of the British and other Europeans.

g) In 1623 AD during the rebellion against his father, Shah Jahan sought help from the Portuguese, which not only was refused, but royalists were helped with gunners. This marked a turning point in favour of the English and the other Europeans nations, against the Portuguese.

h) In 1630 AD the Portuguese attempted to get the Dutch and the English ousted from Surat and, to put pressure on governor of Surat, captured a ship of the Mughals, but English came to the rescue of governor.

i) In 1632 AD, the Portuguese suffered a humiliating defeat at Hoogli at the hands of Shah Jahan.

j) In 1634 AD, Shah Jahan offered concessions to the Dutch, if they would expel the Portuguese from Daman and Diu, but the proposal was not accepted by Batavia.

k) In 1634 Mathew, the English governor of Surat, met the Portuguese Viceroy at Goa, and entered into a trade agreement. The purpose behind this move seems to counter balance Shah Jahan’s offer to the Dutch.

l) By 1634 the English and the Dutch were well-established as traders in India, and had won prestige once enjoyed by the Portuguese.

m) In 1637, the Mughals besieged the Portuguese ports, Daman and Diu, but peace was made through mediation of Fremlin, the British chief at Surat. The British strategy now was to maintain Portuguese in their possession, so that Dutch may not prey upon them.

n) Sri-Lanka (Ceylon) was taken over form the Portuguese by the Dutch. Batavia became the largest commercial centre in the Far East by 1650 AD. The Dutch East India Company carried silk, indigo and traditional spices to other countries.

After the Anglo-Dutch war of 1780, the Dutch began to cede certain parts of their huge colonial empire to the English.

It was the Dutch, and not the English, who challenged Portuguese first in the Indian Ocean by rounding Cape of Good Hope in 1595 (which British had done in 1591), depriving Portuguese of their hold on Straits of Islands. In 1603 they blockaded Goa, and soon afterwards in 1612 made themselves masters of Indonesia. In 1619 they built city of Batavia on the site of Jakarta. They seized from Portuguese best Islands of Archipelago. Amboynas, the richest Island in southern Moluccas, was captured in 161858, they expelled Portuguese from Sri-Lanka (Ceylon) and in 1652 they captured the Cape of Good Hope. The great port of Malacca was captured earlier in 1614. Thus it was the Dutch and not the English who brought the downfall of the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean.

The religious fanaticism of the Portuguese consumed a good part of their energies; monks and friars flocked to the east, establishing churches, converting locals, which brought resentment of local population and rulers but they also did much to spread education.

The English as well as the Dutch now took to preying on the Portuguese trade in the Indian Ocean due to the latter’s weakening power. In 1599 the English declared that they had perfect and free right to trade in all places where Portuguese and Spaniards had not established any fort, settlement or factory.

The Dutch had 15 voyages to the East between 1595 to 1601, and in 1602, combined several companies for trading with India into Dutch United East India Company (VOC) with powers of attack and conquest. The Dutch government supported the company in all its undertakings, subsidized its expeditions and made it a semi national concern.

English-Dutch Rivalry.

Causes of rivalry were numerous. The foremost being:

a) Dutch, who were sole distributors of Portuguese goods in Europe and Baltics found themselves in a difficult position, reached java themselves and entered European market. The Portuguese eastern trade had already been dwindling since 1580 and the Dutch assuming monopoly of the European market, increased prices of spices in 1600 AD. The British therefore formed the East India Company in the same year.

b) The Portuguese were a losing power in early 17th century and the Dutch started ousting them from their possessions, with the help of the local populace who had grievances against the former owning to their arrogance, religious prejudices and ill-considered actions. The British wanted a share in the spoils, but the Dutch were stronger due to availability of capital, government support, large number of ships and 10,000 sailors.

c) The British were able to get their full share in the article of pepper, but the Dutch kept monopoly of cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg and other fine spices.

d) The Dutch, besides their naval supremacy had 21 years true between Holland and Spain in 1600 Ad. This freed them from the danger of war in Europe and from any conflict with the Portuguese in the East Indies, and thus were encouraged to oppose the English.

e) In 1619 AD, the Dutch intercepted four English ships, compelling them to come to terms and in the 1619 treaty the Dutch Company was allowed half of the trade in pepper against English monopoly and the Dutch allowed the English one third of fine spices.

f) Four years later the Dutch captured an English ship with ten Englishmen along with nine Japanese and one Portuguese, who all were executed on charges of conspiracy against their possessions in East Indies.

g) In 1653-54 AD the Dutch captured three English ships which had left Surat. One was destroyed.

h) After the Dutch war of 1654 AD, under the treaty of 1665, the British got compensation for 1619 AD massacre.

i) The Dutch captured three English vessels in the bay of Bengal and intercepted ships between Surat and Bombay between 1672-74 AD, but the English were unaffected as they had entered in a series of treaties with local rulers, as well as with the Portuguese, and aimed to oust the Dutch from India as they could not do anything to remove them from the East Indies.

j) The Dutch had established factories in India at Pulicat (1610), Surat (1616), Chinsura (1653), Qasimbazar, Barangore, Patna, Balsore Neaptatam (1659) and Chochi (1663). The number of factories was substantial and well distributed along the whole coast of India. The English, however, continued their efforts to oust the Dutch.

k) The Dutch retained their overall commercial position until mid-eighteen century, with increased power and colonies in the East Indies, Sri-Lanka and the Cape of Good Hope.

l) The defeat of the Dutch in the battle of Bedara (Biderra) in 1759 AD, two years after departure of Brahe, caused the Dutch opposition to the English to collapse.

m) With the establishment of the English rule in Bengal, the English in India gradually usurped the Dutch coastal possessions in 1773, Sri-Lanka in 1782 (under Warren Hastings) and the Cape of Good Hope in 1795. The Dutch were stripped off almost half of their colonies.

Thus Brahe is justified in stating that Dutch troubles in India were caused by the English.

n) In the 17th century the English concentrated more on Indian trade as compared to the Dutch who after the capture of Java, Samatra, Archipelago, Aboyno and Sri-Lanka, concentrated on the trade of these countries and sent shipping expeditions to India, responsible to Batavia, where as the English trade was decentralized form Surat (later on shifted to Bombay); Madras in the 17th century and Calcutta, a third centre, was added at the end of 17th century.

o) The English started their trade factories in India at Surat (1612), Balasore (1633), Lahri Bundar (1635), Madras (1640) and Hoogli (1651), 24 miles north of Calcutta. These were organized under two governors at Surat and Madras in 1661. By 1663 the Dutch had nine factories in India against four of the English, as the English factory at Lahri Bundar was closed. The English, however, added many more factories in the next 94 years as compared to the Dutch. They finally arrived with the defeat of the French in India and the conquest of Bengal.

p) In 1640 AD, the British built Fort St. George at Masulipatam (Madras) and in 1651 established a factory at Hoogly. By 1654, the Portuguese recognized the right of the English to reside and trade in all their Eastern possessions. In 1657 AD, Surat was constituted as the sole British presidency in India.

Brahe’s continuous complaint was that the English every where always caused harm to the Dutch in business and as a consequence the Dutch had to suffer financially.

Short History of Dutch Trade in Sindh.

In 1619 AD, Piter Van den Brocks, director of VOC (United Dutch East India Company) factory in Surat, reported the possibility of trade with Thatta and Diol-Sindh or Diewal-Sindh (Lahri Bundar), via the river Indus from Lahore. The overland route to Sindh from Surat was only a month’s journey, but was infested with robbers and wild animals. According to him, Sindh besides textile had abundance of cheap necessities of life, which Portuguese carried to the Persian Gulf countries with large profits.

The English and the Dutch East India companies, however, did not enter into trade with Sindh as it required defeating the Portuguese at Lahri Bundar first, and then facing the un-certainties of volume of trade with Sindh.

In 1623 AD. United Dutch East India Company established a factory in Iran and its first Director Vishich reported about good prices that Sindh’s textiles fetched there.

The British received a Farman from Mughal Emperor to open a factory in Sindh in 1631 but establishment of factory was delayed due to death of one of their leading officials in Surat. The Dutch therefore sent a ship Brouwershaven under command of Gregarious Connlisz to Thatta.

Although the Dutch made a profit of Dfl 14,000, they found famine conditions and miserable state of country. This experience taught them that trade with Sindh at that time was not feasible.

In 1634 VOC in Iran reported that goods transported to Iran from Sindh by overland (probably by coastal) route via Makran had fetched a profit of Dfl 680,340 that year and if transported by sea in Dutch ships, it would fetch a profit of 27 percent to VOC. But the Dutch authorities in Surat were not impressed, due to their sad experience in 1631 AD.

In 1635 the English East India Company opened a factory at Thatta. They captured Sindh’s trade with Iran, otherwise sent by land route. The Dutch come to know of it, but did nothing in response.

In 1652 the Dutch finally decided to open trade with Sindh and Director Pelgromsent Pieter de Bie came with a ship to Sindh. The English apparently though friendly with Dutch, secretly joined hands with the Portuguese and persuaded the merchants not to trade with the Dutch and even tried to induce the notorious pirate Rasy Rama to attack Dutch ships. The Dutch already knew Rasy Rama. The governor of Lahri Bundar was friendly with them and they were promised necessary assistance and same privileges as the English. This friendly gesture may have been aimed at increasing the trade and thereby the revenues, as the situation in the interior of Sindh had caused considerable unrest and loss of taxes to the government.

The Dutch trade with Sindh was short-lived i.e., for only eight years up to 1660. In 1656 they were looted by sea pirates. In 1657 an expedition against the sea pirates was a failure due to adverse winds. In 1659 Vlieland, Director in Iran, returning from there, planned to visit Sindh and was trapped in a storm. He reached Sindh with difficulty by a native ship and by this time the Dutch East India Company was convinced that trade with Sindh was not profitable and closed the Sindh trade. This was also the time when the war of succession between Shah Jahan’s sons had added to unrest in Sindh. The English East India Company closed the Sindh factory in 1662 AD.

The Dutch thought of opening a factory again in 1672 and 1673, but received adverse reports about law and order situation in Sindh. The Nawab of Thatta, for example, paid Rs.12,000 to 14,000 annually to the pirate Raja Rana, settled on a swampy island in the Indus Delta, to clear the sea of Sangani pirates (probably Kutchi pirates) and this Nawab also paid Rs.10,000 to 19,000 annually to a Baluchi chief, to make roads clear between Thatta, then the capital of the Lower Sindh, and the rest of Sindh. The Dutch therefore dropped the idea of trading in Sindh.

Just before 1700 AD the Dutch East India Company again thought of opening up trade with Sindh, buy textiles of Sindh for Basra and Iranian market, but the VOC did not open trade with Basra until 1707 AD and therefore trade with Sindh did not materialize.

Failure of the English and the Dutch to have a meaning full trade with Sindh, in the whole 17th century, was caused by the chaotic conditions in the whole of Sindh discussed in other paragraphs. However the right time for opening trade relations with Sindh was soon after 1739 AD, which the Dutch missed and came late by another 18 years.

In 1757 AD, VOC again sent their ships from Batavia with Java sugar, cinnamon, cloves, macis, zinc, iron, tin and lead; fixed minimum prices of all goods for sale, except sugar, fixed maximum prices of good to be purchased for the return shipment and also fixed exchange value of the currency. The merchant in charge of the ship de Pasgeld, was Brahe who, on way back to Batavia (Jakarta), had a disaster and was punished by fine. He had left a journal of his trade with Sindh, during the year 1756-57 AD. This forms the main part of this book.

Although the East India Company (of the English) received a farman from Ghullam Shah Kalhora in September 1758, it appears from the account of Brahe that the English East India Company’s ships had been visiting the ports of Sindh for some time and their ships and arrive while he was at Oranga Bundar, some where, in the first ten days of January 1757, bringing powdered sugar in canisters and bags, iron, tin, lead, zinc, raw Bengal silk, Malabar pepper (Piper nigrum), sappanwood, sandalwood, cochenille, cardamom, elephants tusks etc.

Articles of Import in Sindh.

By powdered sugar brown cum white crystalline sugar is meant, as the one manufactured locally from cane was unrefined sugar called Gur, which forms thick lumps, has high moisture content, and would ferment if kept over a long period. It has low shelf-life. Powdered unrefined sugar called Musti, similar to Gur is slightly more refined and has longer shelf-life than Gur, but stored in bulk for some time, it would ferment too. Powdered partially refine sugar, having brown and white crystals, came from java (Indonesia) and it did not ferment. It was a product of precipitation of sugar juice in a similar manner as first stage of sugar manufactured in modern factories, where it is further refined to make white sugar. As Gur and Musti do not have a good shelf-life, powdered brown-white sugar (partially refined), was imported in large quantities. Both Sindh and the Punjab having non-perennial canals in 1757 could not have raised sugar-cane, a perennial crop, except in limited areas, along the western Nara canal, leading to the Manchar Lake.

Candy sugar was another item which was needed in small quantities. By it Gur and Musti are meant by Brahe.

Pepper and spices formed another important item of trade. By pepper, Piper nigrum or black pepper is meant. It grew in Indonesia, India and Sri-Lanka and was imported in Sindh then, as it is being done now.

In the 15th to 18th centuries word spices in Europe meant more than 200 articles of the East, including textiles, but in this case, by the trade with East, they meant clove, cinnamon, nutmeg and other fine spices used in food.

Nutmeg was needed in small quantity i.e., 2 sockets of mais. Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans. Hautt) belongs to Myristicoceae family and dried kernel of its fruit is used as a fragrant spice.

Clove (tropical dried flowers of my ritaceous tree Eugenia aromaticus Linn) is added to some foods for fragrance and it is commonly used even to this day, but cloves had special use and possibly peculiar only to Sindh. Dry whole clove flowers as imported, were embedded within stitches of Ralis or bed mattresses; then these Ralis were folded and stored. The flowers produced a peculiar clove fragnance and when Rali was occasionally spread on the bed, the sleeper enjoyed its mild fragrance, which was then and still considered stimulant. It was also used for generating fragrance in female dresses, provided these were stored long enough, with a few cloves put between various layers of clothes. Use of such Ralis and clothes was limited only to certain occasions like marriages and for beds of important guests. Its use in food was proportionately much less. Use of clove for this purpose has come down after Independence.

Cinnamon (cinnamomum zelanicum Nees) of Lauraceae family was used comparatively less in Sindh and Brahe is right that the Sindhis accepted wild cinnamon bark in place of good cinnamon of the Sri Lanka, as they were not especially fond of it, as in Europe or certain other parts of India. Wooden parts of cinnamomum camphora of the Southeast Asia were imported in the South Asia for various uses.

Camphor was used very little in the medieval Sindh, in the 18th century and so was the case before Independence, as artificial substitutes of it were used on various occasions. As an insect repellant it was introduced by British in the 19th century in the South Asia.

Curcuma (Curcuma longa) is reported by Brahe to have been produced in Sindh in large quantities and there was no market for it. Curcuma belongs to Zingiberacea family, grows in India, but I have not been able to confirm about its production in Sindh.

Sappanwood was imported and dumped in large quantities by the English at the Sindh port and Dutch found no market for it. Due to war of succession between Noor Muhammad Kalhora’s sons there were inland troubles which affected trade of this item. It was surplus at Diewel-Sindh (or the new port which had come up at the delta of the Indus, after erosion of the Oranga Bundar and before establishment of the Shah Bundar by Ghullam Shah Kalhora, a few years later). Sappanwood came from Malaysia, and yielded red color dye, which was used for printing in the textile, industry. Brahe found no market for sappan wood as it was plentiful in Sindh. Local babul wood yields same dye and it is in plentiful supply in Sindh. Brahe mistook babul for sappanwood. Since babul (Acacia Arabica) is thorny tree of the sub-tropical hot deserts, it was not grown in many parts of the South Asia and therefore sappanwood was imported for extracting red dye.

Cardamon (Elettaria cardamomum Linn of Zingiberacea family) is a fragrant spice from South India and South China.

Sindh also imported metals like Iron, steel, zinc, tin and lead. It seems that there was regular local supply of copper and it was not imported. Source of this copper is difficult to ascertain, but Lasbella hills probably had copper mines. Zinc was used for manufacture of brass, an alloy of zinc and copper. Brass had a unique position in Sindh for manufacture of table-ware. Although clay pottery was used in the medieval times by the very poor, but side by side brass-ware too was used even by the poor. The rich invariably used brass table-ware. Tin was used for lining or tinning of cooking utensils made of copper. Occasionally lead was added to zinc and copper to produce leaded brass, but ancient Sindhis probably understood the danger of using lead in tableware and so they were tinned. Use of leaded brass was limited to drinking glass, but before use, they were lined with tin and were periodically relined. Brassware was not tinned. Tin smiths also added lead to tin to seal metallic joints. This was done as lead was cheaper than tin. Some decorative items and articles of worship by Hindus were also made from alloy of tin and lead. Durable statues for temple worship were made from brass or bronze. Bronze is a tin and copper alloy and is also called gunmetal, which was used for temple bells. Brass had another common use for manufacture of small bells put around neck of domestic animals and ankles, feet and necks of riding animals like horses and camels and also bullocks used for bulk-carts. To reduce the cost, occasionally lead was added to manufacture these bells. Large guns, made of gunmetal were imported and there is no evidence of their being cast in Sindh in first fifties of eighteenth century as Kalhoras had made efforts to get guns from the Europeans. Supply of arms was one of the reasons why various rulers developed friendly relations with the Europeans.

Steel had special use of making swords, which were in Sindh since antiquity. Axes, knives, scythes, butcher’s long knives, hammers, plough shares and tools for day to day use of carpenters, blacksmiths, masons etc., were made from steel. Iron was used specially for jointing wood work in boats and housing, door hinges, clamps etc. Screw tyhpe locks also were made of iron. Only rich used screw type locks made from brass as they looked more attractive. Most of these devices gave place to factory-made articles of same nomenclature in the rural Sindh in the twentieth century.

Brahe considered export of these metals to Sindh a profitable trade.

Cochenille and benzoin appeared to be quite in demand in Sindh according to Brahe. Cochenille is probably the same as cochineal, a red dye used in cosmetics.

Benzoin was redish brown aromatic resin having a vanilla-like odor, used in manufacture of perfumes and cosmetics, and as an expectorant and antiseptic. Both co-chenille and benzoin were used by Brahmanas and yogis for applying on forehead. Hindu women used them for tika on forehead and women in general used them as components of face cosmetics. Benzonian also came in white color, and it was only white type which was in demand in Sindh.

Chinese velvet and Coromandel Chintze of various back grounds were two other items which were sold at Rs.5-6 and 7-9 yard respectively, an exorbitant price according to 18th century standards. One would think that these costly items were for use of royal ladies, but rich noble-men wore them too and this is why prices were high but quantities imported were small.

Mirrors were another items produced in Europe and exported to the East, Sindh included. Glass industry was well established in the whole of Europe in the 18th century.

Chinese gold was imported in Sindh. The South Asia has been the importer of gold since antiquity. According to Pliny in the 1st century 550 million sesters of gold came to the South Asia annually in exchange of local products from Roman Empire. In the South Asia use of bullion was for ornaments of all types. Any exports surplus to imports, during the year brought large quantities of silver and gold which disappeared from circulation in the form of ornaments. The Chinese gold, here means pure gold which Chinese exported in return for imports, was preferred to European coins which had copper mixed in them, to make them hard for circulation without wearing out fast.

Silver wire had special use in leather work. The Sindhi shoe makers used silver thread on local made male and female foot-wear. Its use was very common among the Muslim community of Sindh up to the independence. The silver wire was about 1 to 1.5 mm wide and about 0.2 to 0.3 mm thick. It was embroidered on leather with the help of very fine punch with sharp flat head and laid in geometrical patterns, the most common pattern of which was like woven ropes of cots, swings, chairs, decorative workmanship in bricks for grills and wood work of Sindh. This common pattern has now been preserved in Sir Agha Khan Medical University’s grills and screens. Almost all male and female shoes had silver wire-work on them in fine geometrical patterns.

Elephant tusks were used for decorative pieces, bangles and ornaments.

Vitriol stone or calcium sulphate was imported. By pouring hydrochloric acid on it, sulphuric acid was produced. It also had medical uses.

Mercury was imported in Sindh. It had medical uses. In Aura Vedic (Indian) and Greek systems of medicines, mercury and arsenic were used for cure of syphilis and also for manufacture of aphrodisiacs. Wrongly administrated they are fatal and may have been cause of death of many elites of Sindh, including, Ghullam Shah Kalhora, 15 years after Brahe’s visit.

Fragrant sandal wood (Santalum Linn. Of Santalaceae family) was imported in Sindh and had market for manufacture of small boxes of objects of art. Due to its fragrance it was also used in temples and stands for reading the holy books of Muslims and Hindus. It was produced in India.

Surat yellow was a lead compound yellow in color, used as dye in the textiles and as paint for buildings when mixed with other ingredients. It was also used by the Hindu priests for painting their bodies.

Paatjee is probably what the Sindhis called Pat (a silt textile).

Coconuts are imported in Sindh since time immemorial. They are not used for extracting its oil but are chipped and eaten as dry fruit. Powdered and mixed with other dry fruits, fried wheat flour, sugar cand many other spices. It was used as a snack in the medieval pneumonia, cough and throat troubles in the winter.

Peplemoel de Gallanje probably was a flower of some plant used in the medicines.

Radix China, I have not been able to find what it is.

False glasses pearl were used in the imitation jewelry.

Rolls of Chinese textiles considering their cost may have been silk cloth rather than cotton as Sindh was one of the leading exporter of cotton textiles since many millennia and could not have imported cotton textiles.

Potessory and Armozijnenare are fine textile probably of silk used for lining. The Bengal muslin was imported in Sindh and these may have come from there or else where.

Raw Bengal silk is silk thread used in embroidery.

Gumlac or Lakh used in printing of textiles and layman work in wood. It was produced in Sindh, but supply may have been short due to internal war of succession and may have been imported for the Thatta weavers. Copper’s knives are ordinary pocket knives.

Surat capock is cotton from Surat. Sindh produced its own cotton which may have been in short supply due to change in river course from old alignment along Hala, Oderolal, Nasarpur, Shaikh Bhirkiyo, Tando Muhammad Khan, Matli and Badin to the present course west of Hyderabad. The imports of textiles and cotton from Surat, Bengal and China may have been to overcome shortage and keep textile industrial workers busy.

Iron and steel were only to be sold to king as they were primarily used in making arms, shields and swords.

Sabres were heavy one edged swords usually slightly curved used by cavalry. These were manufactured locally, but may have been in short supply due to the war of succession, where every Kalhora prince and every Baluchi sardar had to raise army and equip their soldiers.

The king’s men had offered the Dutch a good price of Rs.13 to 14 per picol of iron. Brahe refused to sell it to the king, on hearing that the king had purchased iron and lead form the English (East India Company) for Rs.10, 000, some 3 years back, but had not cleared arrears.

Brahe reports sale prices of woolen (carpets) and camel hair fabrics (Plemiet and Grijnen) to the Afghan merchants at Thatta. The Afghans needed these fabrics due to freezing winters in Afghanistan and woolen cloth was invariably imported form the East India Company but camel and goat hair fabrics are made in Sindh and beside saddlery for camels, horses and donkeys these are used by Baluchis for tents and carpets. The Dutch mayhave purchased them from Iran or Sultanate Oman (Muscat) for sale elsewhere.

Articles of Export from Sindh.

Traditionally Sindh exported rice, textiles, cotton, yarn, indigo, salt petre, hides and skins, domestic animals for milk and meat, fuel wood, herbs, oils, oil seeds, ghee (or molten butter), leather articles, wheat and other small items.

Brahe mentions following articles of trade which the English East India Company’s ships took to Bombay, in return for their goods:

- Assafoetida, a chemical probably washing soda.

- Chaels or shawls made of wool.

- Koetnies, some ready made textile ware.

- Rice, coarse as well as fine rice was produced in Sindh.

- Leather, average area under irrigated cultivation in Sindh had varied between one to one and half million i.e., about 7 to 11 percent of present area and rest was pasture land on which buffalos and cows were raised. Goats and sheep were raised in the Thar and the Kohistan and so were camels. Buffalos and cows produce best skins available in the South Asia. It was used locally in saddlery, camel upholstery, shied, butter and liquid storage containers, shoes and articles for domestic use.

- Ghee was produced by melting butter, derived from milk.

- Wheat was produced on the preserved moisture in the riverine dood plains.

- Rape oil was raised as dubari crop in rice fields.

- Indigo was produced in the central districts of Sindh i.e., Khairpur, nawabshah, Dadu and Larkana.

- Various kinds of textiles, coarse as well as bleached, with some fine designs printed on them. Designs were also woven in fine geometrical patterns.

- Salt petre, it is by-product of the cow/buffalo sheds. Buffaloes like to silt on their own excreta and in absence of it they suffer from barn sickness. In a decade about 20-30 cms thick compact layer of material is produced. Manure and urine contain nitrogen potash and phosphates and small rains fall in Sindh helps to keep the layer moist. Aerobic and anaerobic reactions produce potassium nitrate, if manure is allowed in such a situation for a few years to decompose. Salt petre is separated from such rotted manure by dissolving the soluble of this matter into water, boiling it and finally by precipitation. It is used in gun powder. In the seventeenth century, its trade amounted to 10,000 mounds annually. Nowadays potassium nitrate is produced in chemical plants at cheaper rates and manure is used as fertilizer more profitably.

- Cotton was trade mostly in form of fabrics, but raw cotton and yarn too are exported. Cloth was in the form of very fine cloth, coarse cloth and printed cloth, of various grades, colors and quality. Major centers of the cotton weaving were Rohri, Sukkur, Kandiaro, Sehwan, Nasarpur and Thatta.

The other products reported by Brahe were:

- Borax.

- Sal ammoniac.

- Opopanax.

- Assafoetida.

- Goat bezoar.

- Lapistutiae.

- Raw silk.

- Raw silk jemawaars.

Sindh’s competitor in the trade was Surat. It traded in cotton fabrics, muslins of Sindh, Punjab and also of India. Its weavers and traders were Memons and Khatris, who had migrated from Sindh after 1530 due to tyranny of Shah Beg and Shah Hassan Arghoons and, in a century of comparative peace, Surat became more important than Thatta in the above items of trade.

Endless Textiles of Sindh.

According to Brahe, Sindhi textiles had no standard width or length and, still more, their peculiar feature was that the Sindhis weave them endless like a belt. This was true of Sindhi handmade cloth which was being manufactured in Thatta, Nasarpur, Sehwan, Larakana and number of other places up to 1947, specially during the World War II, to meet shortages of cloth and cater to the needs of Indian National Congress members who were compelled by the party to wear hand-woven cloth. But, ironically enough, in the thirties and forties thread was invariably machine made and some times imported. The loom consisted of two vertical poles of a bout 20 yards, but length was invariably measured by foot-steps of the weaver or a wooden pole. Thread was wrapped around the two poles by boys running end to end, usually following anticlockwise direction and two women, squatting near the poles, kept thread edge to edge until it was one yard wide. Then started vertical threading or weaving on both sides of the loam, usually by two men, who sat on two stools. This produced endless cloth, about a yard wide and about 40 yards, measured not by scale but the length of fore-arm, i.e., from tip of middle finger to elbow, assuming that two fore-arms lengths would make an English yard.

Taxes.

It was customary for European traders to send gifts to the king of Sindh. Although the East India Company had no factory in Sindh but they were sending gifts to the king every time their ships visited the Sindh port. The English governor of the East India Company at Bombay also sent gifts annually. These were regular, year after year, irrespective of visits of ship. If gifts were not sent, probably, more custom duties were charged. There was a fixed custom duty on each item based on the sale value.

Weights and Measures used by the Dutch East India Company and English East India Company, in Sindh.

One mound (mand of Brahe). = 75 Dutch Ibs.

One mound. = 82 Seers (cheers).

One Seer (cheer). = 29/32 Dutch Ibs.

1 Gaz (meter) [Gues of Brahe]. = ¼ Dutch Yard.

Canisters were metallic or wooden boxes and preferably the former and were sealed

For storing spices, Pico was a measure of weight = 42 heavy seers (cheers)

Man-i-Pakka. = 73/1.25 Dutch Ibs.

Historical Geography of Sindh in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.

Deiwel-Sindh, Debal or Deval, a church or probably a Jewish synagogue (as the Persian Jews had a colony at Debal from 3rd century AD onwards to 12th century), was located at the present site of the Banbhore ruins and probably was the Barbarican of the Romans and the Alexander haven of the Greeks. It was burnt by Khawarizm Shah in 1226 AD and has not existed since then, except probably as a small settlement. Before 1300 AD, or around it, major hydrological changes caused Indus to change its course from north of Makli Hills and south of Banhbore to a new course south of Makli Hills, leading towards present site of the Sakro town. Debal was abandoned and a new deltaic port established and named as the Lahri Bundar. (Lari comes from Lar or the lower Sindh). Foreign shippers and traders called it by Lahri Bundar as well as Diewel or Debal-Sindh. Ibn-e-Battutta visited Lahri Bundar in 1333 AD.

A peculiarity of the Indus River is its advancing delta. The river carried with it an annual silt load of 400 million tons in bygone days, when it was discharging 60,000 cubic kilometers of water annually. Silt load varied and was as much as 0.6 per cent in summer or inundation season. This silt deposited along the sea shore and land advanced into sea. An average advancement of 240 kilometer long coast by 3 kilometers a century is recorded. But this is not the end; the channel in the deltaic area changes its course frequently due to formation of silt islands in front of it at the point where it enters the sea. The port therefore, cannot be located at the mouth of the river but is located many miles inland, where river is considered more stable. Normally the port is located 15 to 20 miles inland, but the advancing delta does not allow the port site to remain stationary. Port is to be shifted periodically. During the last century present Keti town was a bundar and was called Keti Bundar. Today the bundar/bander or port is some ten miles south of its original site, a century ago, and this was also the case with Lahri Bundar, which changed sites a number of times from 1300 AD to 1758 AD. During Aurangzeb’s governorship of Sindh and Multan in 1848-52 AD hydrological changes at the delta made the Indus river desert Lahri Bundar and it became an unimportant place. A new port named Auranga (Oranga Bundar) was established. This port lasted for a century, when a new port Shah Bundar was established by Ghullam Shah Kalhora. It was an important port for a few decades when finally came up the Keti Bundar, as the British saw it, after conquest of Sindh. The old ports on the same estuary of Indus off sea-creek kept trading for some times and such was the case with Lahri Bundar, which Manucci visited in 1657 and saw a Portuguese factory and a Catholic Church there, although Oranga Bundar had been established. No wonder therefore the old names, Debal or Dewal or Lahri lingered on in the memory and the ports at various sites have been called by such names, by outside travelers, visitors and even by some locals. Diewel-Sindh of 16th and early 17th century is Lahri Bundar. That of second half 17th and first half of 18th centuries is Oranga Bundar and after 1760 AD, Shah Bundar.

A local pilot was needed to lead the ship to the port Oranga Bundar (called Diewel-Sindh by Brahe), because of sand bank in front of it. This sand bank is caused by deposition of silt carried by the Indus, which when enters the sea, losses velocity and deposits silt. Ships have to enter the river form the site channels and need a guide or pilot familiar with depth of width of the channel.

The ship de Pasgeld left for Karachi (Karratje) on 10th October 1756 and sold sugar at the highest rate that it was able to obtain since it left Batavia.

Karachi (Karratje) was a small town situated on the bank of Salt River (i.e., the Liari) two miles inland. The old city of Karachi, as the British conquered and saw in 1839 was situated near Liari river, having a mud fort, with one gate and the other Kharadar or brackish water gate facing Native Jetty or the sea. It was 2 miles inland from sea, having about 20,000 inhabitants. The word Karratje confirms the opinion, that there existed a small settlement in the 16th century called Karautshi on the sea coast, at about the same location. The past of the city, can therefore be traced to the late Samma period or at least beginning of 16th century AD.

Karachi was populated by Banyaz and Sindhis. The formers (banyas) were traders and the latter (Sindhis) plied small boats to the Persian Gulf, Muscat, Cambay, Kanarese, Kokan, and Malbar coast (carrying articles of trade for the Karachi banyas). These Sindhis also called Makrani are now settled around the old boundary of city in Baghdadi, Liari and Khado. The conquest of Karachi by the British in 1839 and cheaper methods of transport of good, to the same places by bigger steam driven ships, put this whole community out of business. They then resorted to catching sea fish in their country boats and supplied dried fish to Sri Lanka and the other places. Opening up of rail and ice factories in Karachi made transport of fresh fish inland possible. They are in fishing business even today.

Brahe’s ships did not touch Oranga Bundar established by Aurangzeb a century earlier, as the delta had advanced and heavy ships could not travel up to Oranga. They had to be left down streams where the river was deep.

A settlement, village or Dera is mentioned. Dera is common word in Sindh for a village. In this case it would be Dera or residence of Jam Saheb or Jam Saheb Jo Dero in Sindhi. Jam Saheb in this case probably was Jam of Kakarla who was a strong land-owner in deltaic area. The place of his residence may have been Kakarla and may also have been known as Jam-jo-Dero. The word Dera is used by Samma tribes, like Rato-Dero, Nao-Dero, etc. Baluchis use Tando which is prefixed rather than suffixed rather than suffixed like Dero.

Brahe came to Oranga Bundar on 8th December, by a local flat bottom boat or dinghi as it is called in Sindhi. He dispatched a letter to the ruler of Sindh on 10th December 1756 to his residence at Nasarpur, announcing his arrival and seeking permission to carry out trade. Kalhora’s capital up to 1754 was Khudaabad 8 miles south of Dadu. Due to hydrological changes in the Indus, with a branch of river flowing to the west of Khudaabad, the capital had to be shifted. Hydrological changes continued and river did not stabilize and, therefore, a number of new capitals were built, one after another. Muradabad near Nasarpur was built by Sindh’s ruler Muradyab Khan in 1756 AD. This was short lived. He shifted to Ahmedabad near Sakrand in 1757 AD, and in 1758 AD Muradyab Khan again built a new capital Khudaabad-II, 2 miles north of Hala. In 1760 another capital was built, 4 miles west of Nasarpur at Shahpur. In 1758 it was finally shifted to Hyderabad. Brahe’s letter of 10 December 1756, therefore, was addressed to Muradyab Khan at his capital Muradabad near Nasarpur.

Brahe report that in 1757 AD, the city of Thatta was situated 2.5 miles inland form the river. He also visited Thatta on 6 February 1757 after a 5 day journey from Oranga Bundar. The distance could not have been more than 30 miles from Thatta but along the serpentine course of the river it was about 50 miles. The inordinate delay in reaching the destination may have been because the hired flat bottom boat moved upstream by the side of the river. Its movement was further hampered by the lack of southwestern winds, and prevalence of northern winds against the direction in which the boat moved. Goods were transported by bullock-carts or on camels from Brahe’s landing on the river bank to Thatta, a distance of about 2.50 miles.

Local Names of Agents, Traders, Governors etc.

Brahe had engaged a broker named Annedermee (Anand Ram, a common Hindu name even now) at Muscat for trading in Sindh. Anand Ram spoke Portuguese and acted as translator between the Dutch and the local merchants.

Brahe traded with Banya Nebanbounmal (Nibhaiyomal is common name among Sindhi Hindus to this day).

The Shah Bundar or the governor in charge of the port Oranga Bundar is named Cattanne (Khatyan). Khatyans are originally Khetrians from D.G. Khan’s western border with Loralai and are settled east of Duki. They came with Kalhora, helped them in occupying Sindh, and were given high positions in Kalhora government. The descendents of this Cattanne are settled 5 miles northeast of Tando Jam in the village, Arif Khatyan. The Shah Bundar was sympathetic to Dutch and was ready to get them permission to establish factory, constructed buildings and raise flats at Oranga Bundar. This kindness of the Shah Bundar was meant to increase amount of trade with Sindh and thereby increase income form taxes. Since Sindh had become a tributary to Afghanistan and had to pay heavy amounts each year, the Kalhoras had to increase their revenues by different methods.

Radia Ram the merchant who came to see Brahe, may have been Rijjoo or Ram a name common among Sindhi Hindus.

The king of Sindh is named as Misaayp, whose reply was received by Brahe on 23rd December 1756. The king was Muradyab Khan and was also called Mian Saheb.

On 20th January 1757 Brahe met two Afghan merchants Goupieramme (Gope Ram) and Radja Runal.

On 23rd January 1757 Brahe sold two canisters of cloves to Gouidia Dassen and Goudia Gio. The two names could be Forth Das and Gorth Devu, common names in Sindh.

Private trade by employees of East India Company.

It is well known from the East India Company’s records that the Company’s high official entered into private trade in India, made large sums of money in the 17th and first half of 18th century, took money home, used it for buying properties, starting manufacturing establishments for export and, it is this money, which by 1760 brought an economic revolution in England called ‘English revolution’, which in turn lead to ‘Industrial Revolution’ of mid-19th century.

Brahe has mentioned a good example of this private trade by the Governor of Bombay, who sent two of his private agents to the Diewel-Sindh and sold at lower prices than the Dutch. He laments that the Sindhis cannot distinguish between the high quality of goods of the Dutch and low quality goods of the English governor of Bombay and thus the Dutch cannot sell these goods in Sindh.

Law and order situation in Sindh in 16th and 17th centuries.

There were chaotic conditions in Sindh during 16th and 17th centuries and some improvement had taken place from 1701 to 1772, when situation deteriorated again. The causes and extent of chaotic situation is discussed by present writer in an article ‘Sindh’s struggle against feudalism 1500-1843’, published in the journal of Sindhological Studies (winter, 1979, pp. 26-67). It may be referred to for details which have been collected from a number of rare sources. The causes for chaotic conditions in brief were:

a) Shah Beg Arghoon’s conquest of Sindh from Sammas, uprooting all urban population, to replace them with his people form Sibi and Qandhar, caused sis-satisfaction and resulted in a large scale migration of educated people and artisans to Kutch, Kathiawar, Gujarat and Arabia.

b) Since Samma tribes formed majority of population in Sindh and were farmers in Sindh, the rebellion started in the rural areas, with consequent government action.

c) This affected agriculture which depended on canal irrigation. Since canals needed clearance year after year their disuse for short time multiplied the silt clearance, irrigation and water supply problems. The people, specially Sammas tribes, became pastorals whereby they could make some living and also get away from organized government action.

d) On conquest of Sindh by Mughals, Akbar imposed taxes which were too high for canal irrigation system of Sindh and which needed one person of population per acre of cultivation. After high taxes in kind the balance crop yield could not support the total population and people refused to pay taxes by taking up arms. Private tribal armies and cavalry were raised and operated in different areas.

e) Revolt in the central Sindh (Sehwan Sarkar) in themed seventeenth century reached to such a degree that law and order collapsed complete and local tribes enforced their own taxes and local governments, under tribal heads and tribal laws.

f) By 1680 AD Mughals were compelled to accept rule of local tribal heads, by giving them official designations, if they collected and paid taxes.

g) This encouraged other tribes, and a leading one of them, Kalhoras, slowly usurped the whole Sindh between 1701 to 1739 AD.

Law and order situation was so bad that trade and traffic by river and land was not possible without paying taxes imposed by local tribes, specially the Sammas in the Indus plains and Baluchis in south western hills.

The information given by Dutch from their limited stay in Sindh tallies with the factual position.

Bibliography.

1. Aitchison, C.U.A., Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sanads Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries, Vol. VI, Calcutta, 1876.

2. Danvers, F.G., History of Portuguese in India, 2 Vols., 1965.

3. Foster, W., Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of Great Mughal, 1915-19, 2 Vols., Hakluyt Society, 1921.

4. -----------------, English factories in India, Vols. IV, 1930-33, V, 1634-36, VI. 1637-41, VIII, 1646-50, IX, 1651-54, X, 1655-60, XI, 1660-64, 1906-1932, Oxford University Press, London.

5. -----------------, England’s Quest for Eastern Trade, London, 1933.

6. Haig, Sir Wolseley, Cambridge History of India, Vol. VI, Calcutta, 1935.

7. Maclagan, Sir, E., The Jesuits and the Great Mughal, London, 1932.

8. Manucci, Miccolao, Storia do Mogor (1653-1708), Vol. I, translation W. Irwine, London, 1907.

9. Maumdar, R.C., History and Culture of Indian People, Vol. IX, Marathas, Bombay, 1974.

10. Mukerjee, Rise and fall of East India Co., Lahore, 1974.

11. Moreland, W.H., India at the Death of Akber, London, 1920.

12. -----------------, From Akbar to Aurangzeb, London, 1923.

13. -----------------, The Shah Bundar in the Eastern Seas, J. Royal Asiatic Society, 3rd Series, London, 1920.

14. -----------------, Akbar’s Land Revenue System, J. royal Asiatic Society, 3rd Series, London, 1918.

15. Sorley, H. T., Shah Abdul Latif of Bhit, Oxford University Press, London, 1940.

By

M. H. Panhwar

AN INTRODUCTION TO WILLEM FLOORS BOOK. "THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY IN THE 17TH AND 18TH CENTURIES"

| Tribute |

| Resting Place |

| Books |

| Articles on Sindh |

| Technical Atricles |

| Activities |

| Photo Gallery |

| Videos |